Years ago when my dog, Josh, became ill he was diagnosed with several tumors. The initial diagnosis was a UTI, pancreatitis and colitis, but an X-ray taken as part of diagnostics was cloudy. The ultrasound clearly showed tumors and a slow bleed from one of them. It was the last thing I expected.

I don’t think there is anything worse than going from a waiting room to a small private room so a doctor can give you bad news. When she closed the door I asked, “Am I going to cry?” Her response, “Probably.”

What took place next was a conversation about Josh’s age, diagnosis and options. When I said to her, “He is twelve years old. I am not going to put him through surgery. And even if it is cancer, I’m not going to put him through chemo or anything else. I won’t do that to him, or me.” She completely supported me by saying, “I think you’re making the right decision.” It changed our discussion from “quantity of life”, what options do we have to prolong Josh’s life, to “quality of life”, how can we get him feeling better so that he looks forward to go for a walk, playing and eating. This began our discussion of palliative care.

I left there thinking, why is it easier to have a quality-of-life discussion with my vet than my doctor? I believe part of it is we are much more attuned to a pet not living as long and that we, as owners, are the only ones who can make an end-of-life decision for them.

So I asked Josh’s vet, “Why is it easier to have a quality of life discussion with you?” Dr. Reichard, suggested, “Maybe because a vet’s approach is more of a whole life approach? We take care of the entire animal rather than breaking out into specialties that don’t talk to one another. And we take care of a pet from the time they are a puppy until old age. We know the whole life story of the dog and the owner. I’ll tell you though, we pay a price in our emotional investment. Veterinarians are either number one or two in suicide rates for doctors.”

Then why is it so difficult for human doctors to have substantive discussions with their patients about how they want to live out the end of their lives? I asked a colleague who is a physician why this is true. “We are trained to fix, to heal so letting this training go is often viewed as a personal defeat. Then there is the culture within American society that tells us we do everything we can, at every cost, to prolong life. The quality-of-life winds up at the bottom of the list. Also, we know that outside of palliative care, there is only so much we can do. Add to that the feeling that people view you as giving up on them, that you don’t value the life they are living as an elder or they are offended when you have an end-of-life conversation. This is true for the patient’s family as well. From a doctor’s perspective, it can be very difficult to have these conversations.”

In his book “Being Mortal”, Atul Gawande explains how “mortality is not taught in medical school and there is almost nothing on aging, frailty or dying.” Because of this, doctors are reluctant to give a specific prognosis, even when pressed. They offer hope with a treatment that they believe is unlikely to work, because they see death as a failure. “Hope is not a plan, but hope is our plan.”

And yet he goes on to say, “People who had substantive discussions with their doctor about their end-of-life preferences were far more likely to die at peace and in control of their situation and to spare the family anguish. It’s the meaning behind the information that people are looking for instead of the facts.”

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services now offers a billing code which one would hope would incentivize physicians to have these conversations. But the cloud of failure often means they do not, or they have a social worker or nurse practitioner have the discussion. This is what happened with my mother, despite my asking him to have the conversation with her because she trusted him. Which means, the responsibility for instigating talking about the subject often falls on the family. And when siblings don’t agree, starting this discussion is fraught with problems.

One of the best things you can do is create an advance directive for yourself because this can become a means to start a conversation with your elder. Because unexpected things happen in life, don’t wait until you are older to put this document in place and have a family conversation about your choices. One of the benefits of creating your own advance directive is the opportunity to educate yourself on what is involved in some life-saving measures. For example, during CPR ribs are often broken, complicating recovery for frail elders. At the end of life, you don’t feel hunger, so is a feeding tube something you want?

Seeing my parents through their frail years and illnesses, along with my work in the eldercare space, is why I believe in knowing what someone wants for a quality of life at the end of life. But the real lessons for why I have my own Advance Directive and Healthcare Proxy documents can be found in this blog post. I’ve learned a lot about quality of life from my dogs.

Disclaimer: The material in this blog is for educational purposes only. It is not intended to replace, nor does it replace, consulting with a physician, lawyer, accountant, financial planner or other qualified professional.

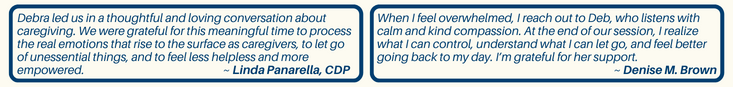

Deb is the author of “Your Caregiver Relationship Contract and “A Relationship Contract for Dementia Caregivers.” Your Caregiver Relationship Contract is available in both English and Spanish. It explains how to have an intentional conversation and the how unspoken expectations can cause problems during caregiving. A Relationship Contract for Dementia Caregivers explains how important it is to learn how your person wants to live their life out and how you, the caregiver are the most important person in this relationship, giving you tips and tricks for this journey.

Click here to learn more about Your Caregiver Relationship Contract or here for the Spanish version: Su Contrato de relación como cuidador de un ser querido. Click here to learn more about A Relationship Contract for Dementia Caregivers.

Deb is available as a caregiver consultant. She will answer the question: “Where do I start?” and find the resources to alleviate your stress. If you would like to invest a half hour to learn how she can help you, please contact her at: Free 30 minute consulting call