Required: Patient navigators who understand the community.

Understanding how to navigate our healthcare system is difficult. When my father was ill, I found it daunting to keep up with insurance requirements, stay on top of new prescriptions and changes to dosages, visit additional specialists and schedule tests. By the way, English is my first language, I drive, and culturally I grew up with the model of Western medicine.

For many people, the biggest barrier to navigating healthcare is language. Combine language with a lack of transportation and you see high-readmission rates within 30 days of discharge from an acute care facility for people with limited English proficiency (LEP). Eliminating these barriers requires deliberate interventions in language, transportation and a sensitivity to cultural norms.

The Robert Wood Johnson Hospital system along with RWJ Barnabas Health launched the Chinese Medical Program through the Monmouth Medical center over ten years ago. The success of that initial program resulted in a Chinese Medical Program throughout RJW sister hospitals. In November 2018, they launched a companion program, the Indian Medical Program at Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital Somerset.

The Chinese and Indian Medical programs target the community, especially senior adults, with little or no English. These seniors rely on family members for translation and transportation. Lacking the English to navigate public transportation and with a reluctance to bother family members, seniors delay doctor visits and treatment.

I had the pleasure of learning about these programs from Angela Lee, Coordinator of the Chinese Medical Program, and Shisha Patel, Indian Medical Program Coordinator. Both women bring impressive resumes to their work, and more importantly, are deeply embedded in the communities they serve. Angela, a Hong Kong native, speaks fluent Cantonese, Mandarin and Toishanese dialects. Shisha, a Gujarat native, speaks fluent Gujarati and Hindi.

Deliberate Interventions are key

If your goal is to lower the rate of emergency room care and to increase the rate of follow-up care, how do you reach out to this at-risk population?

For Angela and Shisha, it starts when a patient is admitted. At that point of contact they have a one-on-one visit with the patient, explaining how the program works, how they can help them and why it is important.

Initially, many are reluctant to participate and it is hard to keep patients in the system. It takes the patient navigator walking with them side-by-side, taking notes, translating and explaining procedures, before they get a clear picture of the benefits. Even so, between transportation and cultural differences, it takes a while for trust to be built. And trust is the real key to these programs’ success of making inroads into non-compliance.

Once a patient is willing to participate in a program, help is available every step of the way. Patient navigators schedule physician office visits, hospital diagnostic testing, explain hospital services, help fill out new patient forms, arrange transportation and accompany patients to medical appointments to translate important information.

Language is the first barrier

Language impacts preventive care, compliance and follow up for people with limited English. When you visit a doctor and don’t have the language to explain your problem, it can contribute to poor patient assessment, misdiagnosis and delayed treatment. If a patient has a hard time understanding what a healthcare provider wants him or her to do, they may miss an appointment or not follow up. When family members try to fill in the gaps, their understanding of the topic and medical terms make the correct translation sketchy at best. Even for those who speak some English, the medical terms may be difficult to understand.

Simple things like filling a prescription can seem unsurmountable when you don’t speak the language. Their patient navigator helps them to understand who to call, where to go, how to talk to the pharmacist and how to take the drugs as prescribed.

Transportation is the second barrier

If you don’t drive, you miss doctor and rehabilitation appointments and you’re unable to pick up medication as needed. When you have limited English proficiency, Lyft and Uber are not viable alternatives.

Cultural norms

Angela and Shisha have found that many of these seniors are resistant to traditional medicine. Culturally, both China and India have a long history of home remedies. Because of this influence, there is a high likelihood that these seniors will self-medicate by taking their blood pressure and, if it is normal, forgo taking medication that day.

Preventative programs are few and far between in their homeland, so they don’t see the value. In addition, they often don’t know their risk for cancer or heart disease because they don’t know the family history.

Then there is the fear of opening a pandora’s box. Many are afraid that the visit to one doctor will lead to more testing and finding out about additional illnesses which is more than they can or want to manage.

Premier service providers

Programs such as these have the flexibility to meet the patient where they are, for example, when a patient must use public transportation, they will figure out the required route and tell them what to do step-by-step, or text the exact address to share with an Uber drive.

Because patient navigators are intimately tied into the hospital system and know the proper channels, they can smooth out the process and take away any confusion. They will find the right specialty doctors, prep patients for a visit, get a clear picture of what needs to be done after the visit, communicate the directions, and then follow up. Angela and Shisha are willing to do whatever it takes, reminder calls or text messages are common.

What solidified the importance of their work for me, were the directions for a CT scan procedure. Cultural differences certainly play a part, but the real problem is understanding. Often this population does not want to ask questions because they feel they will embarrass themselves or their community.

To ensure understanding, Angela and Shisha print instructions for testing procedures in the patient’s native language and correct dialect. Prior to the procedure they have multiple contact points:

- By phone to go over prep for the procedure

- Send the translated prep information

- Follow up with phone calls to ensure the patients stop medications as directed

- Reminder calls the day before

Why it works

These programs work because Angela and Shisha care deeply about their patients. From the first meeting patients see the value of the program, but they continue because their patient navigator is right beside them on this journey. This personal interaction inspires trust and a respect for their patient navigators as professionals. All of which translates into a willingness to see recommended specialists and do what the patient navigators asks of them. The result is more compliance and less emergency room visits.

It’s all about connection

Every Monday morning, the wife of a former patient calls Shisha to say hello and tell her how thankful she is for the help Shisha gave her husband. Occasionally, another patient stops by and surprises her with lunch or a little something to eat.

“They care, the thought behind these gestures really touches my heart.” Shisha Patel.

To learn more about the Chinese and Indian Medical Programs, please contact:

Angela Lee- Chinese Medical Program 908-446-9608 or email: Angela.lee-Gurtler@RWJBH.org

Shisha Patel – Indian Medical Program 908-642-3739 or email: Shiha.Patel@RWJBH.org

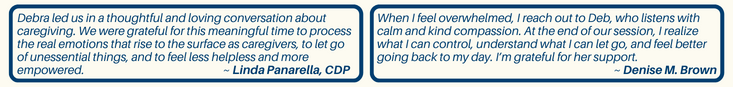

Deb is available as a caregiver consultant. She will answer the question: “Where do I start?” and find the resources to alleviate your stress. If you would like to invest a half hour to learn how she can help you, please contact her at: deb@advocateformomanddad.com